Professors Corey Bradshaw and Barry Brook have examined various scenarios for global human population change to the year 2100 and in doing so address the so called “elephant in the room” for immediate environmental sustainability and climate policy.

Their research was published today in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (PNAS) and outlines new multi-scenario modelling of world human population.

The conclusions are sobering. Even a worldwide one child policy or a catastrophic mass mortality would not bring about large enough change this century to solve issues of global sustainability.

“We were amazed just how insensitive the global human population is to even catastrophic mortality events that could come about from major world wars or global pandemics. Even a 5-year WWIII scenario mimicking the same proportion of people killed in First and Second World Wars combined barely made a blip on the human population trajectory this century.” Says Corey Bradshaw, Director of Ecological Modelling at the Environment Institute.

Instead, the research suggests that reduction on the human population through fertility policy should be a long term goal and in the short term, we should be focusing our energies on technological innovation. Environmental damage is a product of both population size and consumption.

“More immediate results for sustainability would emerge from policies and technologies that reverse rising consumption of natural resources.”

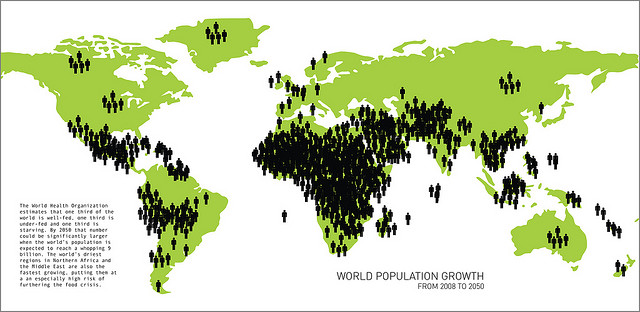

The size of the human population is often considered unsustainable in terms of its current and future impact on the Earth. Recent projections predict the human population will continue to grow to 9.6-12.3 billion people by 2100.

“Global population has risen so fast over the past century that roughly 14% of all the human beings that have ever existed are still alive today – that’s a sobering statistic,” says Professor Barry Brook, Chair of Climate Change at the Environment Institute. “This is considered unsustainable for a range of reasons, not least being able to feed everyone as well as the impact on the climate and environment.

Reduction of the human population should be a long-term goal to reduce environmental damages to our life-support system. But how long would this take?

Current growth of the human population has enormous momentum, to the point that even extensive wars or global pandemics will have little effect on the final population size in 2100. Fertility reduction through family planning will be a slow process that will take centuries to reduce the human population to below today’s number. Family planning could however result in hundreds of millions fewer people to feed by mid-century.

“Our work reveals that effective family planning and reproduction education worldwide have great potential to constrain the size of the human population and alleviate pressure on resource availability over the longer term. Our great-great-great-great grandchildren might ultimately benefit from such planning, but people alive today will not.”

However, continuing the trend towards a global reduction in human fertility will not overly burden the working component of society because as the average age increases, so too does the number of dependent children decline.

“Often when I give public lectures about sustainability science, someone will claim that scientists are ignoring the “Elephant in the room” of human population size. While there needs to be far more discussion on this issue, our models clearly show that it is a long-term solution rather than something that can be addressed quickly.” says Barry Brook.

“The corollary of these findings is that society’s efforts towards sustainability would be directed more productively towards reducing our impact as much as possible through technological and social innovation,” says Professor Bradshaw. He discusses the publication and the sticky issue of population growth over at his blog, ConservationBytes.com.

The research has been covered in ScienceMag.org, Business Insider, The Washington Post, The Independent UK, and BBC News amongst others.