Main image: William Shakespeare (c.1564-1616) by William Blake (1757-1827). (c) Manchester Art Gallery

In preparation for the series events in Canberra, Adelaide and Melbourne to celebrate Europe Day 2016, and mark the quatercentenary of the death of William Shakespeare, the National Library of Australia caught up with the keynote speakers Emeritus Professor Ian Donaldson, University of Melbourne, and Professor Ian Gadd, Bath Spa University, as well as Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide, Professor Nicholas Jose, to ask them about Shakespeare, Europe and what they’re working on.

The full Blog can be read on the National Library of Australia’s blog page. Click here to read the full blog.

A lot has been said about Shakespeare in the 400 years since his death. Do you think that there are any new angles or insights to be illuminated at this point?

Nicholas Jose: What Shakespeare means to us is always changing, so there are always new angles. It’s what we do with it that matters. That’s why the 400th anniversary of his death is important. It lets us think about how exactly he went from relatively unknown retiree in Stratford to the world’s most famous author in that space of time.

Which of Shakespeare’s works is your favourite?

Nicholas Jose: I love Twelfth Night. All the moods and emotions are there. It’s a very opal. ‘The rain it raineth every day,’ sings the clown at the end, and that’s no reason not to enjoy life.

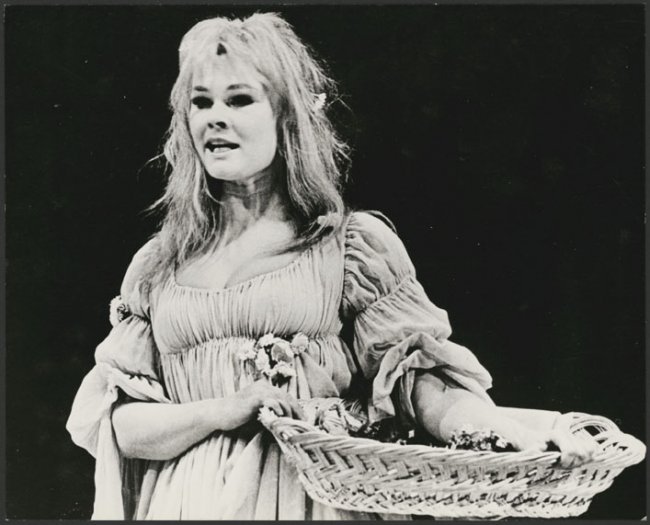

Judi Dench as Perdita in The Royal Shakespeare Company’s Production of The Winter’s Tale, presented by J.C. Williamson 1970, b&w photograph: 19.8 x 24.6 cm, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn3805624.

What does the concept of Europe mean to you, and is it relevant to your writing/research?

Ian Donaldson: In Shakespeare’s time ‘Europe’ was rather a hazy concept: no one quite knew where it began and ended, where to draw its boundaries, how many bits and pieces it contained. Many of these uncertainties are still felt today. There are now 28 member states in the European Union and 47 in the Council of Europe, the two big federations which also confusingly celebrate ‘Europe Day’ on two separate days of the year (5 May for the Council, 9 May for the Union). Some in Great Britain currently believe that ‘Europe’ only begins at—or should be firmly relegated to— the other side of the Channel. A referendum later this year will try to resolve this matter.

Ian Gadd: I’m the son of Swedish emigres, and I was brought up bi-culturally which has meant that I’ve always been aware that politics, society, behaviour, language, even art all look different depending on where you are standing. To be European is to recognise those differences—and to try to understand them.

My research focuses on the history of printing and publishing in England in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries but the book trade has always had an international dimension. In this period, of course, England was not the lingua franca that it is now, so there was a limited market for English books elsewhere in Europe. In the 1680s, for example, a major Amsterdam bookseller refused to sell copies of an important new scholarly work that had been published in Oxford on the grounds that they would not stock English books, while in the early 18th century a German book-collector came to England partly to buy books that he couldn’t find for sale on the continent.

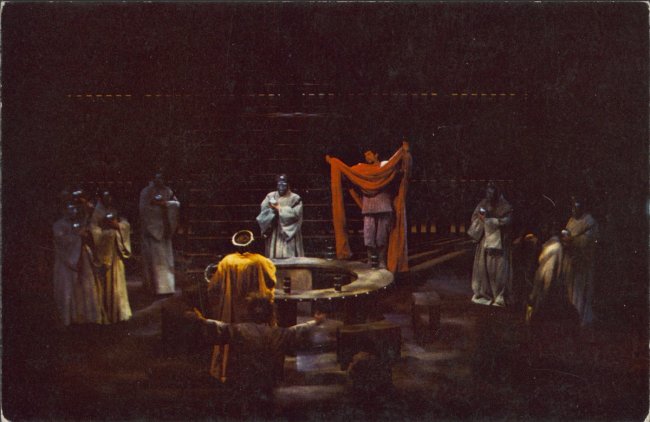

“Macbeth” by William Shakespeare c. 1977, colour postcard: 9.5 x 14.7 cm, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2630411.

Do you see William Shakespeare as a quintessential European?

Ian Gadd: Shakespeare was a quintessential European of his day inasmuch as he, like most of his contemporaries elsewhere in Europe, probably didn’t travel outside his own country. Also, religious loyalties and shifting national boundaries meant that Europe didn’t have the same political familiarity as a term as it does nowadays. That said, Shakespeare would have met European travellers and merchants in London (some, we know, even went to see his plays) and although his knowledge of other European countries was second-hand and sometimes faulty, he well understood that the foreign locations he chose for many of his plays had particular cultural associations for English playgoers and readers.

Ian Donaldson: Like most of his contemporaries, Shakespeare probably wouldn’t have thought of himself as a European, and like most of his contemporaries he seems never to have ventured beyond the country of his birth. Though he set several of his plays in Italy and France these were countries he’d never visited. Other leading English writers of his day—Sir Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, Sir Walter Raleigh, John Donne, Ben Jonson—had travelled in Europe and knew at first hand its cities and customs. They were sometimes amused by his geographical inventions. ‘Shakespeare in a play brought in a number of men saying they had suffered shipwreck in Bohemia’, Jonson remarked, ’where there is no sea near by some 100 miles’.

Why is it appropriate to celebrate Europe Day by marking the quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s death?

Ian Donaldson: Shakespeare, in Jonson’s view, still beat hands down all the writers of Europe. ‘Triumph, my Britain, thou hast one to show/To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe’, he wrote in verses placed at the head of Shakespeare’s 1623 First Folio. Most European countries were happy to accept this verdict, Germany skilfully deflecting any possible slight to their national pride by adopting him as a native son. Shakespeare was ganz unser, ‘entirely ours’, declared A. W. Schlegel, and his countrymen and women were quick to agree. Nowadays more productions of Shakespeare’s plays are staged each year in Germany than in England. Elsewhere across Europe, Shakespeare is generally viewed with devotion. In any ballot for the laureateship he’d probably start as the hottest favourite. He may be the man in these troublesome times (who knows?) to hold Europe together – and settle definitively the date on which Europe Day should be held.

Ian Gadd: Shakespeare has become the most famous author in Europe: not only is his name known across the whole continent (and beyond!) but his work has been read and performed across the continent more than any other. Given Europe’s linguistic diversity, it is striking that a poet and playwright has managed to become such an international figure, but it may well be that the need for mediation in different countries has helped his works maintain a relevance for successive generations. Personally, I think that a playwright—someone who seeks truth through a multitude of voices – is a very suitable emblem for Europe.