The following article was written by Dr Jasmin Packer for the Journal of Ecology, on the subject of her most recent paper – published in the journal – entitled Biological Flora of the British Isles: Phragmites australis.

Reed beds throughout the world have been supporting animal and human populations since the last ice age. These reed communities are critical for bittern and other native biota, create thatch for quintessential cottages, remove waste from water ways, and more recently, supply biomass for bioresources. Rising sea levels now threaten reed beds in some parts of the world, while invasive reed monocultures are expanding in others. Much has changed since Journal of Ecology published its first BFBI account on Phragmites australisin 1972!

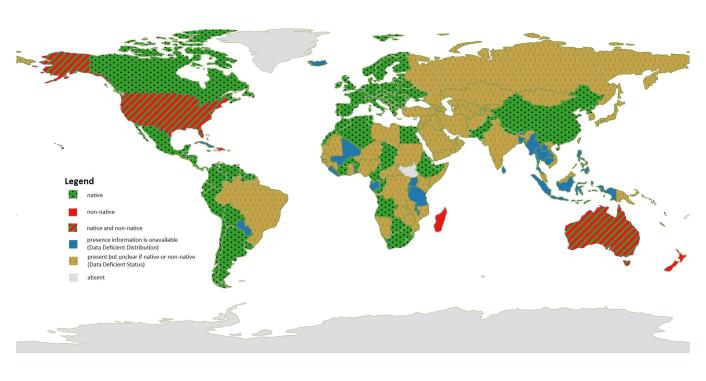

Common reed is a tall-statured grass that is one of the most widely distributed plants globally; it grows from Argentina in the southern hemisphere through to Norway in the north. Although it prefers lowland littoral habitats (with the tallest recorded stands of 5 m in Australia’s low-lying desert oases), common reed copes with a broad ecological amplitude and can occur in moist habitats up to 3600 m (with the highest recorded elevation in Nepal). In these diverse habitats it’s often dominant and has a big impact on ecological processes, especially the succession from water to land ecosystems.

In Journal of Ecology’s recently released Biological Flora of the British Isles account on Phragmites australis, researchers from The University of Adelaide, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, the University of Rhode Island, Czech Academy of Science and Charles University reviewed current knowledge on common reed distribution, taxonomy, ecology, physiology, genetics, conservation and management.

So what has changed since Sylvia Haslam penned her 1972 BFBI monograph? Does common reed look the same and grow in the same places? Are we now better able to predict where it might grow, and how well, than we were 45 years ago?

The major developments (1972–2017) highlighted by our new BFBI Phragmites span taxonomy and productivity through to emerging conservation challenges. Recent research has revealed that the cosmopolitan distribution is a more complex web of overlapping native and non-native ranges (Fig. 2) with varying performance influenced by genome size and haplotype as well as the local environment. Dieback is still occurring in some European stands, while climate-related sea level rise has been identified as a new threat to coastal reed beds. In other more stable and productive habitats, such as roadsides and abandoned fields, monocultures are expanding and are often invasive or of unknown origin. The cryptic introductions and massive expansion of European genotypes to North America are a major concern as these dynamics may be occurring globally.

Over the past 45 years common reed has become an important model species because of its cosmopolitan distribution, ability to grow in diverse habitats, and overlapping biogeographic ranges of native and invasive haplotypes. Looking forward, we predict that “highly competitive haplotypes (e.g. haplotype M) are likely to continue expanding under future global change scenarios” and threaten other native ecosystems where common reed monocultures are expanding. One thing for sure – strategic and collaborative international research is needed urgently to understand and manage these emerging biogeographic challenges. Native reed beds, and the native communities they support, depend on it.

Jasmin Packer, University of Adelaide, Australia