Public Lecture in Adelaide

The great Shakespeare scholar and critic Frank Kermode once described Hamlet – Shakespeare’s profound meditation on death – as ‘the first great tragedy Europe has produced for two thousand years’ (The Riverside Shakespeare, p. 1183). As he dies, Hamlet charges his friend Horatio with the task of telling his story (5.2.297). Horatio obliges, promising to ‘truly deliver’ to the ‘yet unknowing world how these things came about’ (5.2.338, 331-32). Some deaths, it seems, warrant report. And yet unlike the death of his most famous protagonist, Shakespeare’s own death at the age of 52 was marked by silence.

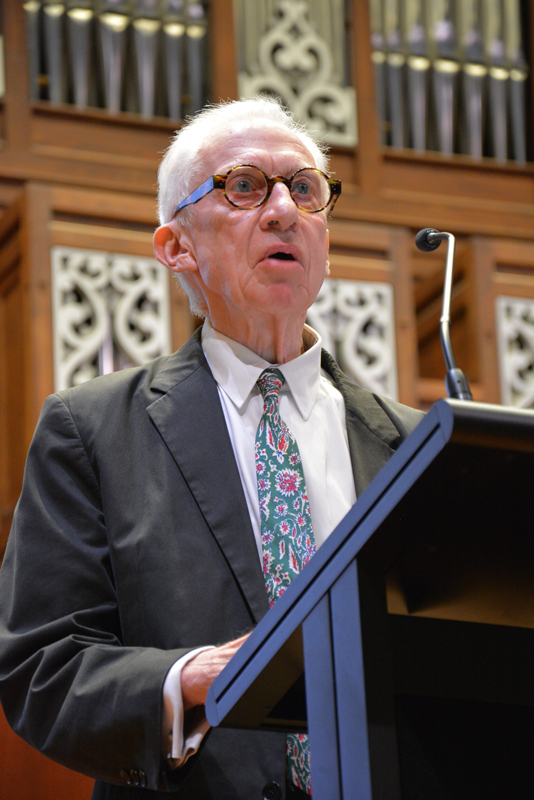

That silence has intrigued Emeritus Professor Ian Donaldson and was the topic of his public lecture – The Death of Shakespeare – to mark Europe Day at the National Library of Australia, in Canberra on 23 April and at the University of Adelaide on 26 April 2016. Professor Donaldson’s lecture breathes new life into Shakespeare by addressing questions arising from the silence that marked his death. Why did the final exit of the man now acclaimed as the world’s most famous writer not attract more resounding applause? How was Shakespeare’s reputation established in the years after his death? How did his words spread, beyond Britain, through Europe, globally?

What Professor Donaldson’s lecture makes clear is that Shakespeare’s fame accrued gradually, and only began to do so well after he was dead. Indeed, his fame at the time he was writing the plays, and building both an acting company to perform them and the first Globe theatre in which to perform them, was never on the cards. Shakespeare was but one of many playwrights during the theatre boom in London at the time, and playwriting was not an esteemed profession despite the patronage of Shakespeare’s acting company, known as The Lord Chamberlain’s Men during the reign of Elizabeth I and as The King’s Men when James I ascended the throne. Poetry was lauded, plays were not: hence, the fame at the time not of the playwright Shakespeare but of Sir Philip Sidney, who successfully rolled the careers of poet, courtier, and diplomat into one. In addition, bills advertising plays did not carry the name of the author but did announce the leading actor as the main attraction: Shakespeare’s main man, Richard Burbage, was famous at the time but the author of the plays in which he acted was not. Nor was Shakespeare’s name recorded in the quartos in which some of his plays were published during his lifetime. Shakespeare’s immediate fame was also hampered by James I’s rather poor aesthetic taste, even though some of the plays were performed at his court. In addition, the play business was not Shakespeare’s only concern – he was a successful businessman in Stratford who engaged in a spot of social climbing, and a family man who suffered the death of his 11-year-old son, Hamnet. He lived a comparatively long life, long enough to see his great rival, Christopher Marlowe, dead at 29 and the light of Sir Philip Sidney’s star extinguished at 32.

In 1623, seven years after Shakespeare died, his friends John Heminges and Henry Condell published the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. In his response to Professor Donaldson’s lecture, Professor Gadd underscores the importance of print for Shakespeare’s fame: here in the First Folio, for the first time, is Shakespeare’s name, a portrait of him, and an introduction by Ben Jonson. Here, for the first time, are 18 plays that were not published during his lifetime, including The Tempest, Julius Caesar, and Macbeth. Some 750 First Folios are thought to have been printed, followed by the Second Folio in 1632 and a Third Folio in 1663. These were items of prestige that contributed to Shakespeare’s growing fame. Of course, as Professor Gadd reminds us, Shakespeare was also a poet. Thomas Thorpe, an unsavoury character whose business it was to steal manuscripts, first published Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets in an unauthorised edition in 1609. The edition was reprinted in 1640 but the sonnets had been rearranged, and in this mangled form they remained for another 150 years. It was not until the world realised through print that Shakespeare was the author of both these 154 sonnets and the plays in the First Folio that his fame was assured and began to spread.

In Adelaide, Professor Donaldson’s lecture and Professor Gadd’s response were delightfully embellished by Adelaide Baroque’s performance of four songs inspired by Shakespeare’s plays: ‘Under the Greenwood Tree’ (As You Like It); ‘The Willow Song’ (Othello); ‘I Attempt from Love’s Sickness’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream); and ‘Where the Bee Sucks’ (The Tempest). Led by Jayne Varnish, Recorders, and sung by soprano Emma Horwood, the songs remind us of the endurance of Shakespeare’s legacy in art forms other than the literary.

By Associate Professor Lucy Potter, Department of English and Creative Writing, the University of Adelaide

Look at the event photos here!

Watch the video of the Adelaide public lecture here: The Death of Shakespeare

Other events celebrating 400 years of William Shakespeare’s legacy

Listen to the audio from the Canberra event here: In conversation: Celebrating Shakespeare

Listen to the radio interview with Professor of English and Creative Writing Nicholas Jose from the University of Adelaide

Read the highlights of Professor Ian Gadd’s presentation in Melbourne on Shakespeare and Copyright here: (c) William Shakespeare

Download a copy of Professor Ian Donaldson’s presentation here: The Death of Shakespeare

The series of events in Adelaide, Canberra and Melbourne to celebrate 400 years of Shakespeare’s legacy were part of the EU Centre’s Europe Day celebrations. The EU Centre for Global Affairs wishes to thank our guest speakers, our audiences, as well as the National Library of Australia for hosting the Canberra event, and the Bailleau Library at the University of Melbourne for hosting the Melbourne event.

The EU Centre also thanks the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800), who partnered with us for the Adelaide event.

Forming a Shakespeare Society of Adelaide

Roger Spence has pointed out that presently Melbourne has the only Shakespeare Society in Australia, and therefore would like to form a Shakespeare society in Adelaide! If you are interested in being part of this, please contact Roger at roger@websa.com.au